Aukus pact delivers France some hard truths

- Published

When they have picked themselves up from their humiliation, the French will need to gather their sangfroid and confront some cruel verities.

Number one: there is no sentiment in geostrategy.

The French must see there is no point in wailing about having been shoddily treated. They were.

But who ever heard of a nation short-changing its defence priorities out of not wanting to give offence? The fact is that the Australians calculated they had underestimated the Chinese threat and so needed to boost their level of deterrence.

They acted with steely disregard for French concerns but, when it comes to the crunch, that is what nations do. It is almost the definition of a nation: a group of people who have come together to defend their own interests. Their own, not others'.

Of course, sometimes nations decide their interests are best served by joining alliances. That's what the US did in suppressing its isolationist instincts in the last century.

But the second painful truth exposed by the Aukus affair is that the US no longer has any great interest in the outdated behemoth that is Nato. Nor does it harbour any particular loyalty to those who have stood by its side.

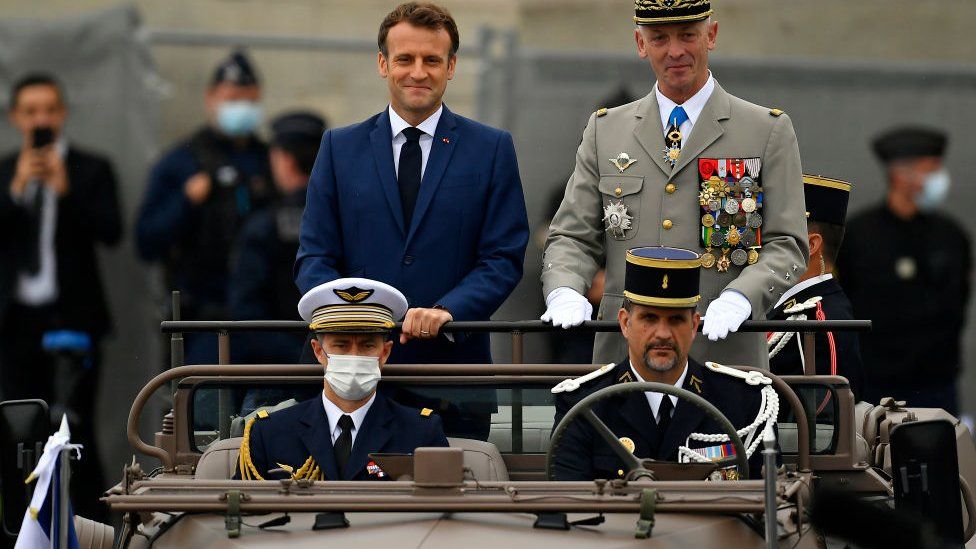

Gaullists in France - and President Emmanuel Macron is one of them - dream of their country as a fully independent power, exercising its force for good thanks to a global presence and nuclear-backed military strength. In practice, and not without considerable reserve, France has bound itself to the US-led alliance because that seemed both moral and expedient.

But now the questions echo around Paris: Why did we bother? What was in it for us?

"This blow came completely out of the blue," says Renaud Girard, senior foreign affairs analyst at Le Figaro newspaper.

"Macron made so much effort to help the Anglo-Saxons. With the Americans in Afghanistan; with the British on military co-operation; with the Australians in the Indo-Pacific. Look, he kept saying, we're following you - we are genuine allies.

"And he made the effort not just with Biden - but with Trump too! All that, and then this. No reward at all. Treated like dogs."

The French will now be re-evaluating their role in Nato. Their military participation in the organisation was suspended by De Gaulle in 1966 and only restored by Nicolas Sarkozy in 2009. There is no talk, yet, of a second withdrawal. But remember, Emmanuel Macron is the man who described Nato two years ago as "brain-dead". He will not have changed his mind.

Australia’s ‘risky bet’ to side with US over China

But the third harsh truth is that there is no obvious other way for France to fulfil its global ambitions.

The lesson of the last week is that France by itself is too small to make much of a dent in strategic affairs. Every four years the Chinese build as many ships as there are in the entire French fleet. When it came to the crunch, the Australians preferred to be close to a superpower, not a minipower.

The conventional way out of the conundrum has been for the French to say their military future lies in Europe. The EU - with its vast population and technological resources - would be the springboard for France's global mission.

But 30 years has given nothing beyond a few joint brigades, a bit of procurement planning and minor contingents from Estonia and the Czech Republic in Mali. For Renaud Girard, the idea of the EU as a military force is a "complete joke".

So what can France do?

Accept realities. Try to form ad hoc alliances (like Macron was indeed trying to do in the Indo-Pacific). Keep pushing the Germans to get over their 20th Century complexes and act like the power they really are.

And keep open a doorway to the British. It may not be the easiest of suggestions at the moment. Relations between Paris and London are at their worst level for many years. The French find it hard to conceal their contempt for Boris Johnson, and many in London appear to feel the same way back.

In the short term, it is quite possible that France will seek to punish the UK for its role in the Aukus affair, says Girard, possibly by scaling back the secret nuclear co-operation that forms part of the 2010 Lancaster Accords. There could be fall-out in other areas too, like the control of cross-Channel migrants.

But the UK's is Europe's only other serious army. The two countries have similar histories and world experiences. Their soldiers respect each other. In the long term, Franco-British defence co-operation is too logical to ignore. That may be the last of Macron's painful truths.

Related Topics

- Published19 September 2021

- Published16 September 2021

- Published16 September 2021